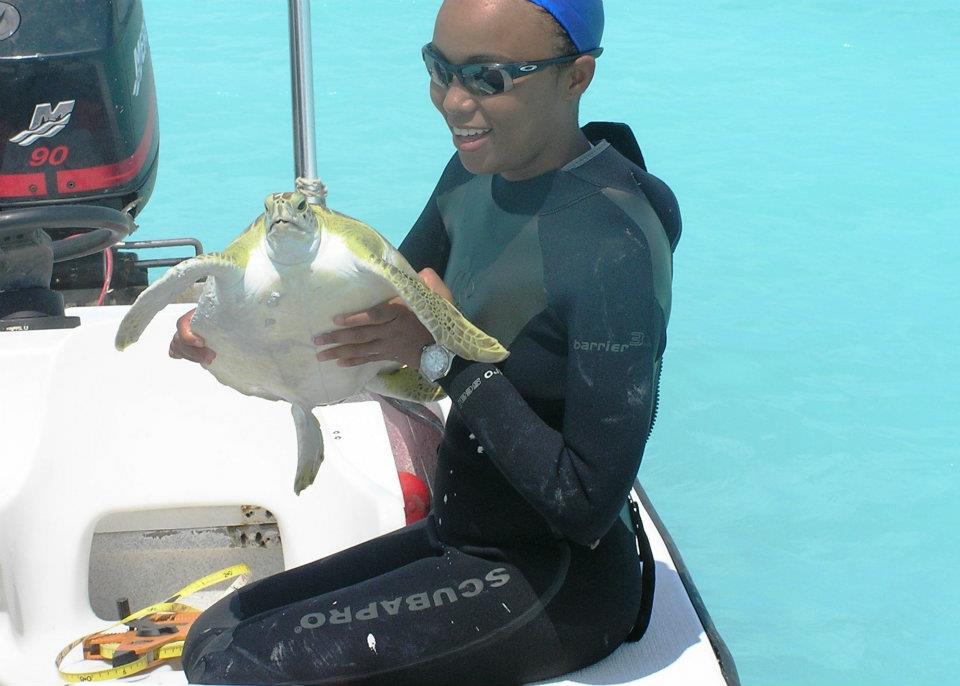

Vanessa Haley-Benjamin is laying the groundwork for cultivated mollusks

Header photo: Fianna Fluess

Vanessa Haley-Benjamin is a woman of many talents.

She’s a marine biologist, New Harvest fellow, and a PhD student at the University of Newcastle where she’s working on the development of cultivated mollusks. She’s passionate about using science to inform conservation efforts and policy measures. Her hope is that the research she’s working on will help sustain and protect fisheries, particularly in her home country of the Bahamas. Recently, I had the chance to sit down with Vanessa to talk about this research and her perspective on how countries like the Bahamas can be included as we scale up the alternative seafood industry:

Listen and follow along

Marika: Welcome, Vanessa. So happy to have you here to have this conversation about your work on cultivated mollusks. Everyone, I’m here with Vanessa Haley Benjamin. She wears many hats– she’s a marine biologist, a fellow at New Harvest, and a PhD student at the University of Newcastle where she’s working on the development of cultivated mollusks. Vanessa, I’d love for you to take a couple minutes to also just introduce yourself in your own words.

Vanessa: I’m a marine biologist that’s crossed over to the molecular biology world. I’ve worked in the conservation field across the conservation spectrum in The Bahamas and wider Caribbean. So I’ve worn many hats. I’ve worked in policy, worked in science, assessed coral reefs, surgically implanted acoustic transmitters in the abdomen of fish to see where they go and then take that research and work to protect the habitats– spawning habitats in particular– that were important for this species so that The Bahamas can protect this multimillion dollar fishery. So taking science, turning that into practical conservation and policy is my past life. So crossing over into molecular biology, hopefully to do the same thing: to help fisheries.

Marika: Yeah. Sounds fascinating. I could talk to you for a long time about just surgically implanting that device– so many questions there. I would love to be able to see where all the fish go. I’d love to kind of hear a little bit more about how you decided to make that transition from your previous work in conservation and policy, to what you’re doing now, which is more bench research focused.

Vanessa: Yeah. The decision to transition from my previous work in conservation and policy to now bench research was really to seek possible solutions to some of the conservation challenges we were experiencing. I’ve always been closely connected to marine resources, particularly to those of the Caribbean and The Bahamas. That was largely in part to me being raised on an island, dominated by the sea, seeing my cousins and uncles depend on it for their livelihoods, and seeing my grandmother and aunts who fed a household from the sea’s bounty. So I have vivid ocean memories, and these memories are really what drives me. And so having worked as a marine biologist, as I said in the opening, across the conservation spectrum for some 24 years, I am internally optimistic that more can be done to help manage fisheries, particularly in the context of climate change, because that in itself just complicates things even more, right? This is when cultivated seafood production piqued my interest. I’d seen articles, I’d kept abreast of it as the technology emerged, and I also had some previous experience in undergrad culturing cells, not for cultivated seafood production, but just culturing cells in general. So the timing actually was perfect as I was reading these new articles on cultivated meat production or cultivated seafood production, and I remember this headline in the local dailies in The Bahamas that read “Conch in The Bahamas can disappear in 10 to 15 years if measures were not taken to better manage stocks.” That really didn’t sit well with me. This is a culturally important mollusk, conch. It’s valued up to 5 million USD in 2018. And on top of that, the conch population in the Florida keys in the US had already collapsed in 1975. So the decline of the fishery coupled with other stressors like climate change, it became even more obvious that more must be done, especially for island nations where the sea is really our lifeline.

Marika: Yeah. Wow. I didn’t realize that that population was already– did you say extinct?

Vanessa: Yeah, commercially it’s collapsed. So it’s commercially extinct, which means that the population cannot support any commercial harvest and they’ve tried several measures, conservation measures, to help populations rebound and it just wasn’t enough. And that’s really due to the life cycle of the conch. They have to reach a reproductive age and there has to be a certain population of conch in a particular area to trigger spawning. Fisheries and overfishing really stresses the fishery and it’s very hard for populations to naturally recover.

Marika: I know you’ve spoken about it this way– GFI talks about alternative seafood as one tool in protecting our oceans and in meeting global seafood demand. So, along with others, such as marine protected areas and fisheries management, how do you kind of see all of these tools, cultivated seafood being one of them, working together?

Vanessa: Exactly. I think working together is the key. So marine protected areas and fishing regulations, as you said, they are common tools to protect and manage fisheries, right? The protection of critical habitats like mangroves and coral reefs help to protect habitats that these fish need to grow from larva to adults. And then the fisheries management component helps us to manage these stocks sustainably. These conservation methods, hands down, are the foundation to food security and thriving oceans. They are absolutely needed. Managing stocks against anthropogenic and climate induced factors has become increasingly difficult over the years. But when we look on an island scale or regional scale, alternative seafood production, I think, can be that bridge, right? It can help to supplement fisheries during extended closed seasons. So closed seasons is a common fisheries management strategy to allow for the recovery of declining stocks. Or cultivated seafood production can produce seafood for those species that are expected to be negatively impacted by climate change and of which communities depend on. Because the science is saying that fish are expected to move northwards from the tropics as oceans warm. And so we are expecting that fisheries that these island communities depend on are now going to shift, the patterns are going to shift. And I think we need to work in anticipation of that. And for this to all work– it sounds like a great idea– but the relevant disciplines should be working together to prioritize species, coordinate development, and implement plans. And I think we need to now have the conversations to see how best we can bring these disciplines together.

Marika: I think that’s a really good point also, because we do see some cultivated seafood startups popping up in Singapore– and that’s where Eat Just is selling their cultivated chicken– but I think really shifting to thinking about this as a conservation tool and working with the communities that are going to be affected most by climate change and the kind of shifts in the fisheries populations and locations as you mentioned. Really, really important thing to focus on. Kind of related to that and something that we think about a lot and that comes up a lot in conversation is around employment, and people who are currently employed in animal agriculture and in fisheries, and what’s gonna happen to them as we transition to alternative proteins at a larger scale. So what do you think– in keeping with the theme of wanting to work in tangent with other conservation efforts– what do you think the cultivated seafood industry needs to do in order to ensure that it’s not only feeding people, not only creating jobs, but it’s also creating jobs where they are needed. And what would those jobs kind of look like? I guess you can say specifically in The Bahamas.

Vanessa: The question– I’ve heard it several times as well– I think it’s one of those ongoing conversations with no real definitive answer, but there’s at least this acknowledgement that it is something that we– and I mean the cultivated seafood industry– needs to be aware of or sensitive to. The question regarding the fate of people currently employed in animal agriculture and fisheries, if we transition to large scale, it’s a pretty valid question and that is really the human element behind our work. I’ve seen that human element working in conservation, working with fishing communities, and it is something that needs to be to the forefront of our minds. And to me, good jobs in the cultivated seafood industry are those that, upon going into communities, understands the community’s needs. It also respects traditional knowledge– because I think there’s much to learn from farmers and from fishers– it offers fair compensation and it is committed to the development of its employees, of course, making it accessible to them, these multi-level positions and roles within the industry.

Specifically for The Bahamas, good jobs in the cultivated seafood industry, to me means inclusion. Not only the inclusion of current fishermen and fisherwomen, but opportunities for current students to develop the technical skills needed to operate a cultivated seafood production company.

Vanessa Haley-Benjamin

I mean, this is something new, it’s something that has high technical skills requirements, and I think providing those opportunities to these communities to be a part of the process is going to be critical.

Marika: I love that idea because it’s not just obviously transitioning folks who are currently working in the conventional seafood industry, it’s thinking forward to the future, how to prepare the younger generations too really.

Vanessa: And I can go back to an example. I’ve always valued the knowledge that fishermen– and I’m sure farmers as well– bring about their industry, about the species that they work with. I was only able to successfully tag and track fish because the fishermen observed exactly where the fish went. They told me at a certain time of year, they’re normally here on the west side of the island. And as soon as the first cold front comes through, they start to move in large numbers on the shallow banks to head to the reef to spawn and reproduce. Now of course that level of detail may not necessarily be required to the cultivated seafood industry, but I’m just saying there’s much to gain by including them in the process and setting up, and you know, what would these regional or island seafood production units, facilities look like? And you know, how do we ensure that the community is a part of it?

Marika: And not exploit that knowledge but bring these people into the conversation. I’m curious about how your friends and family in The Bahamas, how they perceive your current line of work and what they think of cultivated seafood in general.

Vanessa: Some may have never heard about it. And of course I have to explain and upon explaining, I see their mind starts going. They certainly see the need for it. They can appreciate and understand the place we will be 20 years, 10 plus years from now. And that it will certainly be a need and they can see where it can add value to help supplement fisheries. At the same time, there’s this hesitation about growing meat, “I’m not sure how I feel about that” or, being from the island, we tend to like all things natural, so naturally grown, you can catch it out of the ocean and eat it. And then I challenge that thinking by saying, well, what is the state of our oceans today compared to years ago in terms of microplastics, in terms of pollution, you know? And I think those are real concerns as well. And when you try to compare it to things like aquaculture does it, which is not growing meat from cells, but it’s just another tool to produce the food that we need for consumption. It’s something to think about. So there’s mixed feelings, but I think that they do appreciate that there is a need.

Marika: Interesting. Thanks for sharing that. And I think that’s probably the case anywhere you introduce this new technology to folks. That whole what is natural question is one we could debate for years, right.

Vanessa: Absolutely. Yeah, absolutely.

Marika: So you talked a little bit about it already, but I’m just curious what your perspective on alternative seafood as a tool for food security is, especially in communities where fishing is a primary resource.

Vanessa: It’s concerning to me how climate change is changing the chemistry of our oceans. For fish and the tropics, this means a shift in fish patterns and fish are expected to move northward as ocean temperatures warm, as ocean currents shift. And aquaculture facilities will also experience climate-related stresses as well. So this unpredictability is what we should be preparing for, and alternative seafood can supplement limited fisheries and help bolster these fishing communities that really depend on their marine resources as a source of income and also food.

Marika: So you have a really unique perspective, being really familiar with both science and policy angles of conservation, and now you’re more recently transitioning into more molecular research. Are there any kind of connections that you think the rest of us are missing by virtue of not really being plugged into all of the worlds that you’re plugged into? Who’s currently not talking to one another, but should be?

Vanessa: So I can always go back to a conservation perspective, right? Cause that’s where I spent the last 24 years. From a conservation perspective, science informs policy, but intertwined between the two is the social element, which is the people. And having been plugged into the science and policy aspects of conservation and now molecular research, I can see the practicality of the technology, you know. I can see where it can actually be useful in a practical sense beyond just talking hypothetically, right? The alternative seafood industry should be speaking with local, regional, and international NGOs and environmental governing bodies, fisheries managers, and fishermen and fisherwomen. The conversation should be had at those levels. And topics of discussion should include what would the design of a cultivated seafood production system look like to meet the protein needs of a country and to help to manage fishery stocks and how do they work synergistically together.

Marika: Out of curiosity, given where we are technologically with cultivated science, do you think that those conversations should have really started a long time ago? Do you think that it’s time to get started bringing all different folks into the conversation now, do you think we’re doing a good job of it?

Vanessa: I think more can be done. I think conversations are happening on different levels. I think we need to get into the conservation community more– and I think this is probably being done by some– speaking at conservation-related events, speaking at fisheries-management-related events. It was great to see in the new IPCC report though, they did make a mention to alternative proteins, so that’s a great thing. So people are absolutely listening. The more we talk about it, the more we put out the information, the more transparent we are about the process, the more we update the general public on where we are, I think all of that information is important. People are starting to know, people in my profession, in conservation who are working on conch, they certainly know that I’m working on this aspect of conch, and I call them often to ask questions about how to maintain the conch, and information on, you know, embryology and the development of the conch. So I’m doing it already. But certainly more can be done, I think, on those parts.

Marika: You’re a great example of someone coming from a different industry and being able to facilitate – obviously not much different of an industry – but facilitate conversations between different..

Vanessa: Well, the different disciplines right?

Marika: Different disciplines, yes.

Vanessa: Yeah, I live that, I understand the language.

Marika: Absolutely.

Vanessa: For the conservation and science part and learning the language for the molecular part. So yeah, it’s that bridge and those levels of conversation, you know, need to happen.

Marika: Yeah. And we are seeing more and more folks from the traditional seafood industry get involved in the alternative seafood industry, whether that’s more on an industry side or a research side, it’s exciting to see that transition.

Vanessa: I went down to the fish market yesterday to arrange specimen samples with the fishers there and they saw me, they’re like, “Yeah, I remember you from last time you were working on this.” And they’re fascinated and intrigued by the whole process. And I think it’s great to have the conversations during the process. I think that’s critical because there needs to be that sense of inclusion. You don’t want to get to a point and then say, here it is, and you know, this kind of top down approach, but this kind of bottom up and let’s collaborate and work together and, and demonstrate the need or the reasons why we’re doing it. I think that’s critically important.

Marika: Yeah, really bringing folks into the conversation. Especially being able to really utilize their expertise and work together with them. That’s really important. And do they have– are you in Newcastle right now?

Vanessa: Yes, I’m in Newcastle.

Marika: Do they have conch in–

Vanessa: Haha

Marika: Yeah?

Vanessa: No, so the species that I will also be working with — and it can help answer different questions– because one thing I’m realizing about mollusks is that it’s highly variable. So there’s variability amongst species. I can get Pacific oysters here and I can also get scallops here. So I will be working with those and we’ll see how it goes and I will be importing conch. So that’ll be exciting once the conch finally arrive and I can house it here at the marine biology facility. So I will also be taking care of the conch and maintaining the conch.

Marika: I love it.

Vanessa: So I’m doing all around. Yeah.

Marika: I hope to see pictures of them, maybe names or just, you know–

Vanessa: Yeah, I can work something out. I think that can be exciting.

Marika: I love it. Even relative to other forms of cultivated seafood or other species, cultivated mollusks haven’t received a lot of attention. And there’s not a lot going on in terms of research and cultivated mollusks in general. So you’re really kind of almost starting from scratch or have been starting from scratch. I’d love to hear any recent updates on how your research is going.

Vanessa: Yeah, you are correct in saying I’m starting from scratch. And it is for this reason my project is entitled “Laying the groundwork for molluscan cellular agriculture” because compared to vertebrates or even other fish species, much really hasn’t been done on culturing cells per se. Recent updates on my work– well, I am now characterizing the different cell types in molluscan muscle because up until then, I think we knew there’s certain type of cells there, like muscle cells, fibroblast cells, and what I’m doing is optimizing different cell markers to identify those proliferating cells and also to identify stem cells. And that’s going to be important as I enter phase two, which will involve isolating these cells now and culturing these cells. So at first we kind of need to get a lay of the land, understand which cell types are there through the optimization of the markers and then isolating them and getting them to grow.

Marika: Wow. Wow. It’s really wild. It’s really amazing what this technology really encompasses. What would you say are the largest technological hurdles currently, as you’re in between phase one and phase two.

Vanessa: Oh, for phase one and phase two, what are some of the technical challenges?

Marika: Yeah or in general? However you want to answer the question.

Vanessa: Well, for mollusks per se, it’s going to be identifying markers that already exist or have been used on vertebrates and then seeing if they work for invertebrates as well. Can media that other cells thrive in– would that also help and benefit molluscan cells? We just don’t know. And to a certain extent, I know that it has to be optimized for the species that I’m working with specifically. So that’s the greatest challenge there. In terms of the industry in general– cultivated seafood– I think the biggest technical challenge will be scaling up. I don’t doubt our abilities to produce cultivated seafood products that consumers will accept, but sustainably producing a cost effective product at scale will be our greatest challenge, but it’s certainly not insurmountable. I mean, there are many research groups and cultivated seafood companies now that are working on various aspects of reducing media costs and optimizing cell growth to produce the yields needed and organizations like GFI that’s helping to fund some of this research. So it’s optimistic.

Marika: My last question is– and I feel like you’ve talked about it a little bit already– but what does the success scenario look like for alternative seafood and for, I guess all alternative proteins broadly look like to you?

Vanessa: To me, the success scenario is having the ability to sustainably produce alternative seafood and proteins at scale. And this may mean the creation of new seafood protein products, not those that you traditionally are accustomed to seeing.

Success means being able to supplement current or future declining fisheries and more broadly meeting the nutritional needs of a growing global population in the changing climate.

Vanessa Haley-Benjamin

You know, let’s be honest, that’s going to be our greatest challenge in the years to come. And so we have to find these alternative ways to feed ourselves.

Marika: Absolutely. Just out of curiosity, what is the nutritional profile of a conch? Is it high in protein, are there omega-3s? Just curious what that looks like?

Vanessa: It’s protein, like typical shellfish. Certainly omega-3s. I’ve heard that it’s high in cholesterol, but that’s something that’s said locally. I haven’t really tested that in the lab or seen a scientific report, but I do hear that it’s high in cholesterol. So you have to be careful.

Marika: Interesting. And how is it typically consumed? Is it raw or cooked?

Vanessa: All ways. You can eat it raw, like a salad, but it is– the texture, it is chewy. So it’ll be interesting looking at the collagen structure of the meat itself and then seeing how that can be altered to make a more tender meat product. So that should be interesting because usually you have to tenderize it by–we say– beating it where you take like a– and you beat it down and then from there you can make conch chowder, so you can have bits in soups. Or you can put it in a hush puppy, it’s called conch fritter. Absolutely beautiful. So I think it’s going to be interesting, and I think it can be very, very popular and it can be an alternative seafood product introduced to the world even beyond The Bahamas or the Caribbean.

Marika: Yeah, I’ve never seen it on a menu anywhere, so interested in trying it for sure.